Two years ago I wrote a post called What I mean when I say I’m working as an artist. It was an attempt to explain my life to my friends and family (and to myself); a way to take stock of my finances and understand what I needed to do; and a small and early entry into a growing debate about paying artists — a debate that I’m glad to say has since got a much bigger profile. I’ve just done my tax return for 2014-15 disgustingly early in the hopes of arranging a rebate for overpaid tax, so I thought it was time for an update. I feel like a lot has changed in my life — in September 2014 I became a “full-time” artist — but reading the first post I’m surprised by how much still rings true. My understanding has advanced, and my commitment to my work has deepened and become more serious, and I get some better commissions, but my finances and work hours are remarkably similar. I am, however, a lot more obsessed by money. This version uses some of the same text, but is less about explaining what an artist’s life is like and more about looking at where my work comes from and how much money I make.

I’m writing this now for all the same reasons: to explain myself to myself and to the world, and to advocate for better pay. But I’m also sharing it in the interests of transparency. Since I wrote the original post, Bryony Kimmings instigated a project called I’ll Show You Mine, which for a while organised discussions and encouraged transparency about fees and wages. The idea is that if more of us share our finances, more of us understand what we’re worth, how hard it is, and what it takes to live off our art. This post is for other artists, in the hope that they might share things too. But most of all, this is a post for the producers and programmers I work with: Hi! Thank you for all your support and encouragement. Thank you for the opportunities. This is what my finances are like. This is what I live off. I am a moderately successful early-career artist, and I earn vastly below a living wage. Now pay me.

My Work

I make poems and shows and games. I also co-curate the performance night ANATOMY (on hiatus while we try to get the funding to pay ourselves and our acts properly), and occasionally programme or produce other events. Mostly I work in what’s recognisable as the professional poetry and theatre sectors, but I cross over into the performance art end of visual art sometimes, and I increasingly do things adjacent to digital art and digital games development as well.

I finished full-time education just under five years ago. This means that for most purposes I’m an “early career” artist, and in many cases I’m still “emerging”, though some opportunities for those categories cut off after five years, so I hope to have fully “emerged” at some point soon. (I wrote more about what these categories mean last time.) I do get bookings and commissions targeted at early career artist development, but increasingly I put myself into a broader pool of professional artists. My profile is, I think, a little bit higher than peers at a similar stage, mostly because I’m a loud-mouth on social media. Occasionally this leads to work. Occasionally — but, I hope, less occasionally — I suspect that it makes getting work harder.

I’m fully freelance, which on the one hand means I get to write off a lot of things against expenses (a portion of my rent as my home office, my artistic interests as research), and on the other hand means I have a lot more expenses: my office and all supplies, lots of travel, liability insurance, all my NICs, and so on. I also have no job security, no job-related benefits, and no-one’s paying into a work pension for me.

My income is all over the place. A chunk of my money comes from fees from venues and programmers who book or commission me, a chunk comes from paid residencies, a bit comes from my own national funding body grant applications, and a bit comes from box office splits. I don’t have a strong idea of where most of my money should be coming from for it to look sustainable. So far, commissions and residencies have mostly paid my way, but I’m experimenting with building up my ability to tour shows and give workshops, hoping to strengthen my income. It’s still a mess, for now.

I work a six-day week, around seven hours a day. I’m trying to cut it down. To be an artist, I have to plan the art, make the art, organise places to put the art, and find ways to finance the art. These things can happen in any order, and which order they happen in largely depends on whether or not someone’s going to pay me and how much control they want over the product. On average, each month (counting a month as 4 weeks, and a day as 7 hours), I spend roughly

- 4 days writing

- 5 days performing or preparing for performances;

- 4 days writing and answering emails, or doing general admin;

- 4 days in meetings and interviews

- 3 days writing proposals and funding bids;

- 2 days planning and running workshops.

- 2 days writing texts like this

This is a fairly conservative estimate of how much time I spend on the “hard work” bit of being an artist. You will note that of the 24 days of hard work each month, only just under half is spent on what you might think of as the fun bit – or at least the creatively satisfying bit – of making art. Before I was full-time, it was around a third of my “being an artist” time, because everything had to be crammed in; now I’m able to give things a little longer to develop.

I used to have a long-term part-time non-artistic contract, which gave me enough to live off while I developed my practice. At that time, I worked well over the UK’s legal maximum working week (48 hours, or six eight-hour days a week). I do work less now, because anything else is completely unsustainable and results in more weeks of not being able to get out of bed. But I’m still using conservative numbers above, and I’ve only included the “hard work”. Making art also involves a lot of “soft work”. To make good art, or at least to make successful art (by mainstream standards of success), you’ve got to be constantly actively engaged with the world and the art other people are making. (Action Hero have a lovely, empowering blogpost on this subject, among other great advice on living as an artist.) That means that I spend a lot of time

- reading poetry;

- watching performances;

- reading / watching / listening / participating in texts and events about art;

- pissing about on the internet;

- participating in social media.

I didn’t include this stuff because most non-artists (and probably most artists) are likely to sniff at the idea of it being called work. But I mention it because it is part of what I do, and because if work is, at least in part, the stuff we are obliged to do rather than the stuff we enjoy doing, then the work-attitude, the feeling-of-being-at-work, does infect me when I’m reading poetry and watching performances and tweeting and all of that. The flipside of that is that the feeling-of-being-at-play, when I’m lucky, infects the enjoyable bit of my “hard work”.

All of which is to say, this is why many artists will consider themselves over-committed over-workers.

Going “Full-Time”

Back in September I left the regular half-week non-artistic contract to work as an artist “full-time”. I was proud and I was scared. I wasn’t yet making anything close to a living wage, or even the minimum wage, from my artistic work — but I also felt that I’d probably hit an income and career-development ceiling. There’s only so much you can make on half a week, even an overworked week, and a lot of opportunities are closed to you when you’re locked to a particular city for three days in the week. Knowing this, I’d spent time living very frugally and building up a savings buffer so that I could support myself for the first year or two of working as a full-time artist.

I’ve started putting inverted commas around “full-time” for three reasons. The first is that I’ve taken 20-30 days of non-artistic work on temporary contracts since I took the leap: I was in a January slump, had received a lot of rejections with no major pay-offs coming, and was offered good work. I expect this will happen from time to time, and I’m happy with that. The other reason is connected, but runs deeper, and that’s that I regret contributing to the idea that you have to be “professional” and “full-time” to really “be” an artist. You don’t. I’ve chosen to support my art by writing lots of funding applications and commission proposals, but that’s no more legitimate than choosing to support it by working in a bar. Neither is particularly enjoyable labour, and you may find yourself better suited to something like the latter. You also don’t always have to be able to get out of bed. Sometimes you can’t. And that’s OK, even when it doesn’t feel OK: you’re not failing. If you make art, you are an artist. You are already an artist.

The third reason is best put by Alex Swift here. We shouldn’t over-valorise selling our labour. It is an inherently exploitative and alienating social relationship. Work is not the ultimate good of life. We all have the right (and possibly the need) to make meaning in our lives, but to funnel all that into the financial relation of wage labour is foul, for all that I recognise that the right to have work and be paid is an economic necessity. We all deserve rich lives whether or not we can (or want to) work. I would like to live a life without work. I probably never will. But I don’t want to hold “full-time work” as the ambition of my life, because it’s not, and it’s generally not a great ambition if what you want is to have meaning and be well.

Since I went “full-time”, I’ve been able to work a bit less and give myself something like a human scale of time off. I’ve also been able to spend more time on each project, which I hope means I’m making better art, and I’ve been able to apply for bigger and stranger long-term things. I’m currently writing this on down-time from a four-month residency that I’ve organised for myself and got funding for, the kind of thing that’s impossible without having the time free. But it’s not all good. I’ve found myself having to justify myself to myself more: the pressure to make art is greater, and the pressure to make it successful is greater. I am more anxious about my work, which I hadn’t thought was possible. I am more attuned to my status, my reputation, and my need to make the most of every opportunity. I decided I was going to be a professional, but I hate having to act like a professional. I think “professional” is a horrible word to put next to “artist”. “Artist” itself is a pretty crummy word. Both of those terms, like “full-time”, are labels that I still deploy, at arms length, to try and convince people to pay me.

My Income

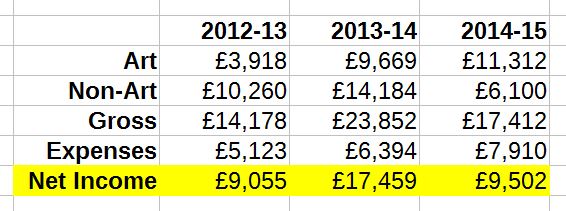

Here’s the tasty bit, then. Here’s what I’ve made for the past three years.

Or, in visual form:

The Scottish Living Wage is £16,300 per year.

The mean income for my age bracket is £22,700 per year.

Some explanatory notes:

- I have a very small student loan for my undergrad (in Scotland, so paid no tuition fees), which I began paying back in my 2013-14 tax return. I had a bank loan for my Masters, but I paid it off.

- I have no dependents, and no allowance.

- I rent, in Edinburgh, sharing with a partner (though for half of 2013-14 and half of 2014-15 I lives alone). My parents now own their house outright.

- Expenses includes a small portion of my rent and energy bills, half my phone and internet bills, and most of my artistic purchases, along with show materials, office supplies, travel and so on. So if you were to compare me to a PAYE worker, you might want to imagine something like an income a little under halfway between gross and net.

- I’m very frugal, but I’d prefer not to be and don’t think there’s any honour in it. I’m still living beyond my income, as I have very gradually built up savings from my non-artistic work for this purpose.

What It Means

This is what I wrote two and a half years ago, and it’s all still true:

I work, and I work hard, for vastly more hours than I’m paid for. For the very little public money I get for my art, I give a lot back: I organise a big performance platform, I give around 10 hours a month as trustee of Forest, a local arts centre, and whenever I do get funding I make jobs for other people. I’m not trying to big myself up – I’m just trying to explain.

I am not doing art because it is easy, nor because it is easy money. I can only be doing it because I love it and because I think it is important.

I, along with many other artists, get furious at the kind of people who comment on articles about arts funding calling us “lazy” and “scroungers”. They have no idea. No idea at all. And I suspect one of the reasons that artists and the industry are really a bit rubbish at explaining what it is their work involves and why it deserves funding is that we’re too damn overworked to take on a major communications campaign.

My finances should look pretty awful to anyone outside the industry. But I do think that my artistic peers mostly have similar balance sheets. I don’t have the feeling that I’m anything unusual. If anything, I suspect I’ve had a little more success than others with my level of experience, though I, like most artists, am constantly berating myself for my failures and for not succeeding faster. In short: I do not feel like my level of work and pay is anything unusual for an emerging artist. I don’t have a good sense from older artists and others in the industry about whether this is a big shift from past decades. I would like to hear from others whether my finances look appalling to them, or whether you too shrug and think that’s just how it is.

It should also be clear that I grab the work when I can, and that I have to be able to manage a lot of projects at once, shift flexibly between them, and be prepared to work strange days and strange hours. I do not have a weekend. This is called “precarious labour” or “cellurisation” or sometimes something else. Artists, or, more horribly, the “creative industries”, have been particular drivers of this economic shift in labour practices. There’s a lot of socioeconomic theory about what it means and I could talk about it for hours, but not here. Bifo’s After the Future and Fibreculture’s Issue 5: Precrious Labour are good places to start reading, and the Precarious Workers’ Brigade is good place to start doing.

I could say that I am only able to do art because I am frugal. But my privilege (class, gender, race) comes into it: it has helped me to get the education which got me the day job; it meant that while I was a student so I didn’t have to do much bar work, which meant could spend my time practising art and learning a lot of organising skills; it provides a support structure so that I can afford to be financially precarious, or at least so that I can feel like I can. I have much lower barriers to being an artist than the majority of the population.

I am very modestly successful in terms of my profile and bookings, for my career stage, and yet this is how hard I have to work for this little actual paid employment. This is the basic reality of trying to be a professional artist. We cannot have a healthy arts culture, or a diverse arts culture, or high quality art, without funding. Without more public funding. There are more precise, more subtle, and more wide-ranging arguments to be made. But I hope that outlining the basics of my reality adds to them.

Demanding Pay

When I first wrote one of these posts, I barely understood my finances. Since then, I’ve run an art project about obsessively tracking them, and though that’s finished I still use YNAB to track all my income and expenditure. I used to think, when I was younger and more foolish, that there was cred in not really understanding how money works and refusing to let it rule me; now I think it’s a vital survival tool and a platform for political advocacy. Money runs the world, and even though it hurts, I want to understand how it flows through me, how it rules me.

I value my time much higher than I did two and a half years ago, and not just because my art is better: it’s also because I’ve gained confidence in quoting what I believe my art is worth. I quote high and expect to be negotiated down. I also believe that to work for free is, in many contexts, to be a scab: that I cannot allow venues, especially publicly-funded venues, to have my time for free, because to do so is to lower the expectations for all other artists. I still work for free in the early stages of project development, but I’d prefer not to, and I still work for box office splits, but increasingly won’t accept it from a publicly-funded venue with paid staff.

I have much less patience now for venues and programmers that don’t pay me. I have never written a shirty email, but I’ve come close, and I do turn things down. Here is something I think about often: that the venues that I work with have paid staff with something approaching job security, but that the artists they programme do not. The people labouring to make the product see much less of the value of that product (not just box office take, but security and pensions and benefits) than the managers of the places the product is made, and this is a 200-year-old economic relationship. When I work for a venue for free, I am almost always generating financial value for them, so why aren’t they paying me? Why are they preferencing the managers of art over artists? Why do we accept this situation? But here is something else I think about often: managers of art are, by and large, on my side. You share my politics, or something reasonably close to it. You are suffering from the same funding cuts as me. In the pyramid of capitalism, you are above me, but we’re both near the bottom. The difference between us is not belief, but power. If you have that power, please do not accept this situation, and be honest about when you are exploiting artists.

I don’t need any more development opportunities. I need to get paid. And so do you.