I’m in a cemetery just outside of Mantayo Seepee / Churchill, Manitoba, on the edge of Kîhcikamîy / Hudson Bay, in Ininiwak / Cree traditional territory. The snow has drifted several feet deep in places, covering many of the stones and wooden crosses, but it’s packed and frozen enough that in most places I can walk on it. I try to step lightly. Just north, beyond the fence, across the snow-drifted rocks, are hundreds of miles of frozen ocean. It’s -15 degrees out, minus a few more for wind chill. Every body surface I can cover is covered, most with four layers, and my cheeks are stinging with cold. There’s a track of something leaving over the drifts — maybe an arctic fox, maybe a rabbit or hare. There are bird tracks too: snow bunting, I think, and maybe some from one of the big, human-sounding ravens that’s been flying overhead. I look down at the gravestones: the surnames are Flett, Oman, Sinclair, Spence. Names from home.

Your correspondent stands beneath a blue street sign reading “Orcade Bay”, wrapped up and looking very cold. Snow underfoot, housing blocks behind, and a grey sky.

We’ve been here for three days, towards the end of the long freeze, well in the off-season, after the best polar bear watching and before the best beluga watching. The national parks are closed, and only a couple of guides are still available. It’s a bad time for tourism and a good time for social history: it’s easier to find folk with time to chat about themselves and about history.

But there’s plenty still here to see: We’ve visited the Itsanitaq Museum, which has an extraordinary collection of Inuit art collected by the Catholic church, and the Arctic Trading Company, which still serves as a traditional trading post for furs and artwork, and where we were shown the beadwork, tufting and slipper-making workshop, but which also sells cuddly polar bears and t-shirts. We ate at Gypsy’s, which does pretty spectacular fried chicken and apple fritters. (Full disclosure: that’s true, but I also got given a donut for saying that.) We drove out to the Northern Studies Centre, past shipwreck, plane crash, and abandoned rocket testing site. We visited the oldest prefrabricated building in Canada, an Anglican church with ornate stained glass. I rode around the boreal forest, right agaisnt the tree line, in a dog sled. We’ve hiked out through the snow to the very point of Cape Merry, where the frozen Churchill River meets the frozen bay, and where we can just see the snowed-in buildings of Prince of Wales Fort across the ice. If we had the energy, the gear and the company, we could walk there straight across the river.

Eight huskies run through the snow, pulling a sled, just visible in the foreground. They’re by a railway track and running into a low forest of spruce and tamarack.

In all the places we’ve visited, I’ve chatted to folk about my research. I’ve talked about Orkney, which, unusually for people halfway round the world, most folk here have heard of (there’s a street named Orcade Bay), about tracking the Hudson Bay workers and their descendants, about wanting to tell stories from here back towards my own home. Mostly, folk are cautiously curious. I grew up on an island of 700 folk, and Churchill has 900, so I’m assuming that word gets around about who the very tall person who’s chosen an odd time to come is.

And as I think about this, I realise what I’m sounding most like, with my too-big smile and my eagerness to talk about my project: the Americans and Canadians who would visit Westray, where I grew up, to look through the kirkyards and local history archives in search of their ancestors. I’m doing it the wrong way round, but it’s just as strange a pursuit, and my preconceptions are probably just as misguided. I start to feel embarrassed, and spend more time looking at the snow.

Blue sky and white clouds above, snow drifts and sparse boreal forest below. In between, an old rocket range: blocky huts of different shapes, one with a metal gantry pointing to the sky.

One big thing is different from when I was growing up, though: Facebook. I join the Churchill Online Bulletin Board, where folk post local events, lost and found items, and general news. At the encouragement of a couple of locals I met, I post there about my project, and soon the comments are filled with people descended from Orkney folk, amused to hear about their namesakes in Scotland. Patricia Sinclair Kandiurin wants her Sinclair castle back and to know what her tartan is; for once, I think, yes, go you, please take the castle, I’ll help.

At the same time, I’m posting about the project in various Orkney groups and reaching out to contacts on Facebook there. The two conversations are mirrors of each other: Orcadians sharing what they know of ancestors who travelled over; Churchill folk sharing what they know of ancestors who stayed. There are Métis, Cree, Dene and Inuit folk here with Orkney names. Folk on both sides of the Atlantic want to hear about their cousins. I’m starting to introduce them to each other, and I’d like to hear about the conversations that result: conversations across climates, communities, and colonisation.

A little black and gold fishing boat, with steps leading up to it and a bench on top, moored and banked in by snow. You can’t tell from the picture, but it was built in Buckie!

I’ve been tracing some more historical connections, too. Pam Eyland told me about Alexander Kennedy Isbister, currently being celebrated during the 140th anniversary of the University of Manitoba. The Métis son of an Orkneyman, he was born on the Bay, but was sent to Orkney, to the school in St Margaret’s Hope, for a few years of education. (Do any Orkney folk know which building was the school in the 1820s?) He eventually worked for the HBC himself, but ended up quitting due to the racial discrimination he faced. He travelled back to Scotland for study at the Universities of Aberdeen and Edinburgh, and became a very successful lawyer working mostly in England. He became an outspoken advocate for progressive causes, particularly Métis rights. And the reason for the University’s celebration is that he left a major bequest for scholarships for students that was explicitly regardless of gender, race or creed: an early mission to diversify the student population and make education accessible to all.

I want to know so much more about this man. What it was like for him as a lawyer in England, yes, but even more so, what was it like for him as a child in the Hope? How was he received by the community there? What was the attitude of Orkney families to the HBC men’s indigenous wives? What was the men’s attitude? Most importantly, what were the experiences of the wives and children? I’ve been told that some of them came back to Orkney and stayed, although I haven’t found specific histories and biographies yet: I very much want to hear more. As well as Orkney folk having First Nations and Métis cousins and namesakes here, who from those people stayed in Orkney, or Scotland more widely?

A tiny soapstone sculpture of arctic terns (inniqqutailaq), on a post, is flying. They are white birds with red feet and beaks and a black cap. The background is red. The artist was unknown, from Naujaat (Repulse Bay)

I keep making comparisons to Westray as I walk around Churchill. There are many connections. The arctic terns that come here in the snow-free summer are in Orkney, especially Papa Westray, in spring: at home they are pickiternos; here one of their names is iniqqutailaq. Both are small communities on the edge of their country; both are now tourism-dominated economies, with the public sector the other major employer, plus folk working in traditional economic activity and a bit of larger industrial work. Both were once a major naval base. Both have a government allowance for distant living. There’s only two main roads. Everyone has a car. Folk have multiple jobs: you keep seeing the same faces in different places; some shops and businesses just operate out of people’s homes. There are locally-organised cultural events that bring everyone together

A lot of this is common to many small rural communities, but I think there are some elements that belong to places on the edge. I fancy, too, that I can see a link between the mannerisms and ways of talking: the driest and most deadpan humour I know, conversations that don’t waste words at all but seem to get everything organised very quickly, a quiet amusement at the things incomers get up to, keen observation, the habit of asking you questions until you work out how we’re connected and placed in relation to each other, which at home we call “speiran at”. As always, this could be as much preconception as reality. And for all those connections, there are enormous differences: bigger than the ice sheets, the two different legacies of colonialism, where the profit was made and where the destruction was enacted.

Left, a wood and metal white Victorian church with a short spire topped with a cross; right, a wood and metal yellow house. In between are big snow drifts and power lines; above, a grey sky; in the far distance, a port factory.

A vast and old looking grain elevator: the main structure, grey and yellow, is a huge box on the left; the dark and tall gantry, leaning slightly, is on the right. For scale, there’s a digger shifting snow right in the centre.

As with Winnipeg, I catch myself taking pride in the connections, and then think hard about in what that pride is based. Here, though, I’m finding more layers and complexities. Colonialism is many-layered and decolonisation can’t be centred around white consciousness and white guilt. There are some folk here keen to hear about Orkney, and who want to know about those ancestors too; there are some folk here who’ve already visited. There are folk like Alexander Selkirk who chose to stay in the UK, but remained attached to Métis identity and Métis rights. The stories are not one-dimensional. Though I’m part of it, how the story continues to be told is mostly not for me to say.

Why am I writing, then? I’m well aware that my own project has its own colonial layers: five Scottish writers exploring the Americas and bringing back tales. I have my own issues to work through and my own learning to do, but I don’t want to take up more space that I should. As I’ve written before, I think it’s vital for Scottish folk (for all folk from colonising nations) to be free from denial about how they have profited and how they continue to profit from ongoing colonial processes, and that involves doing some of this work. I want Scotland to recognise its part in this, and to know that colonialism is a huge and ongoing process (and one that’s different and more extensive, though related, to what the Gàidhealtachd went through), and to understand the extent of the damage and the necessity of reparation. I haven’t talked a great deal about the details of this, because again it’s not my story to tell. Here are three books I’m reading at the moment that I strongly recommend:

- This Accident of Being Lost, knife-sharp contemporary stories and songs by Nishbaabeg storyteller and writer Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. Decolonial love stories and discomforting provocations

- A Two-Spirit Journey, the autobiography of a lesbian Ojibwa-Cree elder, Ma-Nee Chacaby, with Mary Louisa Plummer. An starkly and compassionately honest narrative of trauma and recovery.

- Voices from Hudson Bay, an oral history of Cree elders from York Factory, an HBC post and settlement just round the bay from Churchill.

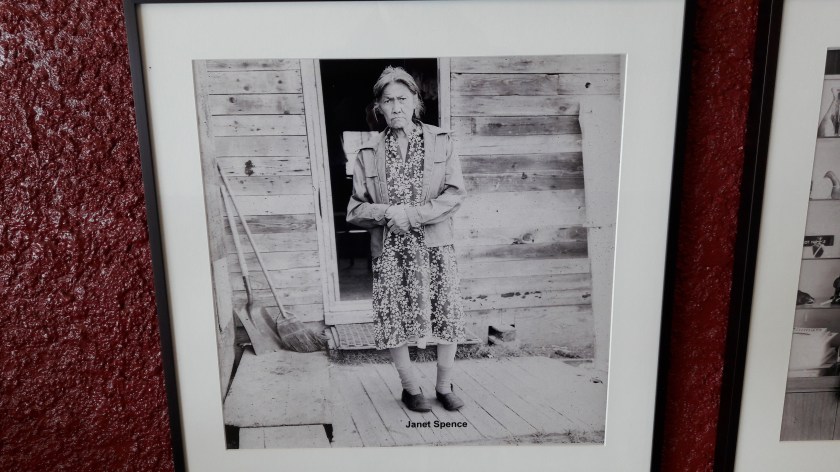

Janet Spence, a late middle aged woman standing in the door of her wooden house. She is wearing a print patterned dress and a short coatel and broom lean in the left of the picture. Her hands are clasped. The photo is labelled at the bottom. The photographer was not labelled in the gallery (Pioneer Gallery, Town Complex, Churchill).

A ten foot high inukshuk (Inuit stone sculpture and landscape marker that echoes a human figure) is central, with smaller stones either side and benches to the right. The background is all snow, white and grey, with land, bay and sky just distinguishable from each other.